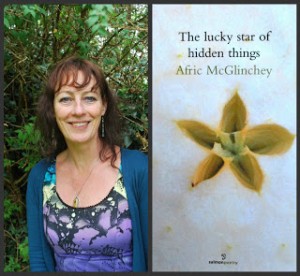

Poet: Afric McGlinchey

Poet: Afric McGlinchey

Title: The Lucky Star of Hidden Things

Publisher: Salmon Poetry

ISBN: 9781908836083

Reviewer: Emmanuel Sigauke

I enjoyed experiencing The Lucky Star of Hidden Things, a debut collection of poems about wandering. Africa is the starting point: remembered childhood, journeys through different cityscapes and the veldt, journeys to differebt shores.

The first section is entitled ‘In My Dreams I travel home to Africa’ and the pieces in there are jewels. Part of it is because as a I read I was looking for the familiar, but primarily because the poet rendered this section with tenderness and a trace of nostalgia, indeed a familiar feeling for one living far away from one’s African country…

In “Birthstone”, the beauty of the language is carried in the memories associated with the concreteness of a birthstone and a ring. The imagery captures a whole universe whose heartbeat are the specific details remembered. The birthstone the persona chose has dazzling beauty: “Its light seduces: from every angle…/..a compass with forty norths, / captured star.” The Africa of the poem is invoked through the Drakensberg mountains, the rivers, then the Namibian shore, tracing the origins of the birthstone, all the way to a table in a room, where the details culminate in the memory of the persona’s father, and further down, the last moments with someone important, to whom she is connected through another piece of precious stone she inherited, a ring, which “reflects you back.”

And we are not done with memories. For me, Zimbabwean (-American), “Yesterday, today, and tomorrow” was treat; the poet takes me back Zimbabwe, and I find myself in Harare, “where buses zig-zag pot-holes/big and black and bold enough to jump into…” The observer captures everything here, whether it’s the “Shona handshakes/loose and triple, palm to palm”, or the Mapostori worshippers, “white-robbed”, gathered under trees. The poem gives a quick Harare 101, the observer’s Harare, the kind of Harare you see as you travel in a Kombi from city center to Tafara, or to Kuwadzana, or to other townships. Then the persona gets more intimate with a Harare life, down to the food, the conversations full of art, the happy moments, the sunshine, but also the dust, the chaos.

There is also a rural side to the Africa poems. They delve into customs and beliefs, and the poet remembers the hardworking village women in “The water bearers”, painting a common picture of rivers, cattle and herd boys, mothers working in vegetable gardens and girl returning from the river, caring “jagoobs” of water. It’s a picture of village industriousness, the beehive of activity that keeps life there moving, even in hard times; the sense of community that makes life bearable. Here the gaze of the poet comes from within, a non-judgmental appreciation of this social engine, capturing the resilience with which the villagers carry on with their activities, but is careful not to romanticize their lives. This is existence; this is hard work, and the sadza at the end of the day is well-earned.

In some of the poems, there are memories of loved ones, such as in “Counting” and “Dancing in the Moonlight”. Again, the sharpness of the memory is captured in the language, the imagery: “you’d move / among birds of paradise…/..yellow lawn crackling underfoot.” Or it could be a little dance, some romance: “Water-shaken / we pad too the rondavel / and you smile / as I fall / into your dance”. There is a certain tender touch in these poems, but you can’t ignore the crudeness of their symbolism.

The humorous piece “Dad’s Manoeuvre” recalls a childhood moment when the persona choked on a piece potatoes and like a hero the dad came to the rescue:

Even now, when I laugh

at the table, a fear races

through me, recalling

the time…/ a potato caught in my throat.

The sweetness of the memory is in the father’s rescue manoeuvre, the urgency with which family laughter turned into sudden sobriety and he squeezed until the piece of potato “shoots from my mouth, and I/ heave in the sweetest breath / alive”.

The Africa section ends with departure, on a plane:

Umbali wa mwisho wa safari –

Have a safe journey –says my screen.

Newsflash of an earthquake in Haiti –

all over our spinning planet,

weather, shudders, rocks, cracks.

The promise of a safe journey doesn’t seem to guarantee a safe destination, as if leaving the sunshine of Africa, we are delivered in the darkness of the unfamiliar: “Africa is melting away, as a caprice of light / flicks up totemic images, / Northern childhood memories.”

Afric McGlinchey’s poetry covers a diverse range of themes, whether she is remembering Africa, or remembering a loved one, or entering or consummating a relationship, as in “Yes”, which echoes James Joyce’s treatment of relationships and deeper secrets, exemplified in a story like “The Dead”. “Yes” is indeed one of the best poems in the collection about passionate love.

One of my favorite pieces is “Totems”, a title that promises something that centers on the totemic poles of cultures in Africa, but when you read the poem, these are not the traditional totems. The persona’s totems are Skype, Facebook and other forms of social media. Then pen, paper and camera, the poet’s friends, in this new totemic mix.

But relationships, just as the promise of nomadism, are full of doubts, reminding the poet of how little our nomadic impulse allows, the transience of some of the feelings we get, yet little can be much, whether the it is the glint of a birthstone, or the remembered moonlight dance, or the memory of a first kiss seeking to compete with the present moment, or, as in “Moving in”, the materiality of an emerging experience, the threat or promise of a new relationship: “Will you have me as I am, then, / with just a laptop and a satchel…/…will you remind yourself/what’s fanciful, what’d real?”

Here is a poetry collection that talks about “impenetrable loneliness”, “nomadic winds”, and reveals intimate moments when “a crack in the sky / is just a small thing”. In some poems the persona is a friend advising against lying to a lover, yet recommending giving half-truths because “disclosure exposes, / creates a stalking fear”.

This debut collection marks Afric McGlinchey as exciting poets whose heart is primarily attuned to her Irish and African experiences, but also points to other experiences. She brings her worlds together, but always leaves room, for discovering new experiences, the true nature of a nomad–to belong, a form of identity always ready to leap into another departure the moment it arrives. There is no better way to make readers curious…