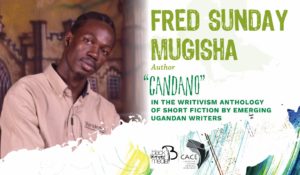

Candano by Mugisha Fred Sunday

No hearing had ever taken this long in the history of the Mvule tree than the one regarding the twelve hectares of land around Kulu Moo between Candano and Olum Jacinto who was feared because of his ironhandedness.

The decade old Mvule tree symbolized unity in this community. All gatherings were held there, whether it was a clan meeting, hearing or drinking kwete, arege, kasese or lujutu brew prepared by the talented women of Cet-kana. Old man Temceo considered the tree his second home because no one drank more than him. Recently however, it was not the jovial drinking that took place in under the beloved Mvule tree, that blood boiling wrangle between Olum and Candano was all that had taken place under this tree.

These meetings convened by the Rwot Kweri of the community had brought no solutions. In many instances Olum did not show up. And when he attended, it ended in a bitter exchange of words between him and everyone else at the gathering. Sometimes, his sons represented him but a son that follows the path of his father, learns to walk like him. He was blessed with seven sons.

But the last meeting proved different. The committee had heard enough. They could not defile their ears with Olum’s insults anymore. Opira, one of the Rwot Kweri’s committee with a close linkage to the ruling stool stood up. All the elders fell silent. He pointed at Olum.

‘Candano’s people farmed that soil. Why shouldn’t he do the same?’

The other elders nodded their heads in assent.

Candano stared at them with utter disgust.

‘We have made fools of this council?’ Opira continued. ‘I will not take part in this any longer. I can use my time and wisdom better where it is needed.’

With that, Opira picked his walking stick and walked away. Shortly, the meeting ended after Olum stormed out, his sons followed suit and gathered nearby. Olum told his sons,

‘The arbitration ends here. Drastic measures have to come in effect immediately.

I will have the land or Candano’s lung.’

Under the Kituba tree, Candano stood up to leave, relieved that the matter had been decided.

***

Candano was as tall as a fully-grown maize plant, huge and well-built with bright round eyes that rolled in all directions like a chameleon’s. He was dark-skinned and his head was shaven as bald as a grinding stone. He often wore a pair of no-smoking khaki trouser that had lost its color with time. He rarely wore shirts so his broad chest was always exposed. He worked extremely hard. At the end of the day he could still be seen carrying big logs of wood from his garden to the homestead. Women envied his wife, Ayaa Josephine, because he even helped her carry water from the well.

Candano’s love for his only daughter Lamaro Margaret was unsurpassed. He spoke at gatherings how much her birth had blessed his life. He liked to tell the story of how Lamaro had saved him from drowning in his dreams. He was a talented storyteller and the villagers loved this story because it sounded so real. Even children enjoyed his company. They liked to follow him around asking him to tell the tale of the dog that got married in a distant land because it was fed meat on its first visit

***

The morning after the clan meeting was strangely cold. Everyone usually went to their gardens after the sun had risen, when the dews on the grass had dropped. The cold morning dews made farm work difficult but Candano and his family were already on their way to the garden. It was time for the first weeding of the young cassava. They planned to plant maize afterwards.

Candano carried three hoes on his shoulder; Ayaa the water pot on her head with Lamaro holding a container of the pasted peas and cassava her mother had prepared the previous night.

Candano hummed and muttered the words of his favorite song, nodding his head.

| Anyaka man leng ma lamoo yaa

Kome ryeny ni dang calo wiro moo nyim Kome vulu-vulu calo ovolo munu Laake ryeny taa, calo tara munu Tibu ne leng ma icol piny pe arweny

Ngat ma ogudu nyani nongo o’ero lweny Ma ikoma wek obedi pe igud ba Ma ikoma degi kolo pe icak ba

Nyapa Rwot woto eno pe igud ba…..

|

The girl is beautiful like shear oil

Her body shines like she smears simsim oil Her body is well built the like Soursop Her tooth shines, like the white man’s lamp Her shadow is beautiful in the dark, I can’t get lost One that touches her has started a fight My own leave it be, don’t touch The one on my body doesn’t want trouble, don’t start The princess is passing there, don’t touch….. |

The variation of his voice made the song enjoyable. His family never tired of it. Ayaa joined him raising her high-pitched voice making the song sound even better. Those who listened as they passed wondered whether it was for his wife or his daughter. Candano never answered questions directly – he loved ambiguity. When the song ended Lamaro looked to the sky screwing her face and asked.

‘Abaa, don’t you think the weather is a little off today?’

‘Every day is a blessing from the gods. Who are we to question how they open

up the skies, my dear?’ Ayaa continued to sing in a low tone.

‘Our folks enjoy farming in this “a little off” weather of yours,’ Candano said. Then he laughed. ‘If you could help us with the song would be nice, don’t you think?’

‘Anything for you, Abaa,’ Lamaro laughed.

***

When they reached the garden Candano found Olum Jacinto with three of his sons slashing the stems of his cassava. Ayaa dropped the pot from her head. Candano threw away the hoes he was carrying and charged towards Olum. Olweny, Olum’s eldest son slashed at him with a panga but Candano dodged this and pushed him away and he fell on his face. Candano grabbed Olum, knocked him down, punched his face and then carried him and threw him on a burnt trunk in the middle of the garden where Ayaa normally piled the weeds that they uprooted from the shamba. Olum’s nose bled heavily. Candano picked Olum’s panga from the ground and pointed it at him with a shaking hand.

‘No, Father,’ shouted Lamaro.

‘What evil has my cassava done you, Jacinto,’ Candano said pointing the panga at Olum. The other two sons, Orach and Oneka, fled.

‘This land is mine,’ Olum said. ‘And I am going to have it whether the elders agree or not…’

‘My great great grandparents farmed in this land. The elders are aware of this. You cannot have what is rightfully mine Jacinto,’ Candano said.

‘The leaves are still wet, son of Moi. A warrior’s blood flows in me too.’

‘It is a cold blood. Which of us is talking with their back against the ground? Don’t bite yourself over my land, Olum. You might choke in your own venom.’

‘Father,’ called Olweny from where he lay. ‘My wrist is broken.’

‘Ever since you claimed my land with insults, embarrassment and pointing fingers, I’ve shown you that I bear no ill intention,’ Candano said heaving with anger. ‘But this here,’ he pointed at the slashed cassava stems, ‘brother of my tribe is too heavy for my back. You have just as many hectares of land as any legitimate son of this soil but the hatred that blinds you towards mine is what I do not understand. I have mouths to feed, so do you. The energy you waste in jealousy and hatred, why not use it for ploughing?’

Lamaro had never seen her father like this.

‘I speak with a leaking heart and if I had a bitter heart as you do son of my tribe, I would have made you inseparable to this land that you crave so badly with that ghost of a child you call your son. And if you haven’t noticed—’

‘Noticed what, Candano?’ Olum asked. ‘You talk of bitterness as if we are blind to the circumstance of your birth… bitterness, me? You’re the bitter one. Where are your parents? Your father was struck by lightning at the drinking joint while your mother was giving birth at your grandfather’s graveyard. Your mother, after your birth, never had the luck of childbirth again. You came with bitterness when you crawled out of her that day. So it is not me “brother of my tribe” who is bitter – we know your story too well Candano.’

‘Don’t force my hand, Jacinto.’

Candano turned in Olweny’s direction and told him to take his father away from his garden before Olum lost his head. Olweny forced himself up, his mouth bleeding, a gnawing pain in his wrist and helped his father.

After Olweny and Olum left, Candano sent Ayaa and Lamaro back home. He told them they could not farm that day. He would stay behind to remove the slashed cassava stems from the garden. The following day they would replace them.

***

After walking one of the two hills towards his home, Olum asked Olweny to release him. He could walk perfectly well. His son was shocked.

‘So you were faking.’

‘Be careful of what you are about to say, Olweny. Today we live, another day we fight,’ Olum cautioned.

Father and son walked home and after crossing the first hill they suddenly came upon Temceo facing the bush by the roadside pushing his manhood back inside his trouser after peeing. ‘Aah, this is a good feeling,’ the old man said. Then, he turned and saw Olum and his son. ‘What are you two fools looking at?’ he frowned. ‘Wait, wait, have you two been fighting? A father-son rivalry,’ he paused, ‘Wulului … Aya-ya-ya-ya-yaaah. You two have been beaten.’

‘You,’ Olweny stammered.

‘Don’t say it. You will spoil the fun. Candano has finally stood up. He could no longer take your hissings, could he?’ Temceo laughed. ‘Wait until the whole village hears of this magnificent event.’ He walked past Olum and his son mumbling a song.

‘We are going to be disgraced,’ Olweny told his father, ‘We need to do something.’

‘Age does not move backward my son, I am no longer swift and my strength is failing.’

‘Luckily, you have a forest of sons. We’ll take care of it. But I have a question. How could you allow Candano to carry you like that?’

His father turned to him. ‘You how could you allow Candano to take your panga? Do know

what might have happened if his wife and daughter weren’t there?’

Just then Orach and Oneka appeared and reported they could not find the other brothers.

‘Mama said they went hunting as soon as we left,’ Oneka said.

‘I don’t remember asking for your brothers,’ Olum answered. ‘Perhaps you two are not men. Perhaps you want me dead. You could have stood by me. But you ran with your tails between your legs like cowards. The hot water burnt your mother for nothing.’

***

Candano collected the slashed cassava stems and piled them on the border of his garden. He tried singing but he sounded like a woman in labour. As he finished up with the last of the stems a very big dark brown snake reared and hissed at him. It had fangs like thorns on a rose flower.

‘Easy there,’ he told the snake. ‘I have no intention of harming you. This is my garden, leave me be. I have no quarrels. I’ve had enough for this day already. I shall go and throw this on the other side.’ He walked backwards slowly keeping his eyes on the snake. ‘Go your way,’ he turned, emptied his hands, then went back for the hoes and walked home.

***

Temceo reached his verandah and felt sad at the emptiness of his home. He thought of two daughters who his wife had taken away from him when he could no longer provide for the family because of his devotion to alcohol. He remembered the stories he used to tell them.

‘… and away the three birds flew, rescued their friend from captivity of the rope set on its nest by the hunters,’ Temceo said out aloud remembering some of the lines.

‘But Daddy, why would they want to capture the beautiful bird?’ the younger girl used to like to ask.

‘I’ll tell you something young girl. Some people are prone to violence and ill intention. They even want to hurt a harmless fly.’

‘Oohh oh…that’s terrible aaargh!’

‘Like the way Olweny’s father behaves towards Lamaro’s father?’ the older girl would inquire.

‘Yes, my treasure. That’s precisely it.’

If they were still with him Temceo thought he would have told them of the latest events. But he would also tell them Candano’s birth story.

Candano’s father had been struck by lightning to death at the drinking joint while he was being born at his grandfather’s graveyard. His mother had gone to clear the bush that was swallowing the grave. After clearing, she sat beside the grave where she had placed her water. She drank some water and rested but in a minute, she was in deep pain. Temceo’s wife who was in the nearby garden heard her cries and ran to see what was happening. She found Candano’s mum in advanced labour pain. In a few minutes the baby was delivered. Temceo cut the umbilical cord and helped Candano’s mother home.

Later Candano’s mother would tell of how she had seen three hyenas nearby before help had arrived. Temceo’s wife confirmed what Candano’s mother had seen. The boy was supposed to be named Olum because he was born in the bush but his mother chose Candano, because there were no people around her when the boy came out. Candano meant absence of people. Women were not supposed to name children, but after the boy’s father was struck by lightning what could she do.

Temceo also liked to tell his daughters the story of the neighboring village Ayugi and the bad harvest after their farms had been attacked by swarm of locusts. Their wizard had then told them to kidnap a virgin from the village for sacrifice to get a good harvest. When this happened the village arranged for a rescue mission. The sister of the kidnapped girl reported that six big men had kidnapped her elder sister. The village sent Candano by himself and he returned with the girl by nightfall. Nobody knows how he managed this. ‘Six big men, six like this,’ Temceo would put up six fingers to show his daughters.

‘He brought back the girl all alone. His courage was rewarded with a cow for saving a life. As a warrior myself, I know that to save a life you must take a life.’ The children would look at him with great silence.

‘What’s the matter?’ Temceo would ask his imaginary children. ‘I don’t understand what courage moves him. He’s not ordinary. Now allow me to sleep. Thank you very much.’

***

After the sun eventually emerged. Candano decided to have a bath in Kulu Moo, where the water was cold. He needed to cool his heated brain. The water at Kulu Moo flowed down the valley from a hill and was shielded by rocks.

After his bath Candano walked towards his home and even from a distance sensed something was wrong. He found Ayaa rolling on the ground as if someone had died. Her left arm was badly bruised. He ran towards her and held her tight.

‘What happened?’

‘She’s gone. Lamaro is gone.’

‘It can’t be, she was in perfect health this morning. Nothing was wrong with her.’

‘No, she …’

‘… this can’t be happening to me. Oh God why—’

‘She was kidnapped by Olum and his sons …’

‘What?’

‘Those two boys who were at the farm this morning, plus other two came and took her away …’

‘Why do sons of men want to take away my life?’

‘They carried her after beating me up.’

‘I have done nothing wrong but farm in a land that belongs to me.’

‘They said you should give up the land …’

‘Or what?’

‘We’ll never see Lamaro again.’

‘They can have my land.’

‘Please, save our daughter.’

‘When I’m dead.’

‘Get me my hunting gear Ayaa. It’s in the corner of the inner wall.’

‘Yes, Moi,’ she replied. Ayaa went into his hut and brought a crescent-shaped bow and

a leather pocket bag full of smooth arrows. There were also two sharp knives. Candano knelt before his wife and she patted him on the back and he rose up and asked which way Olum and his sons had gone. She pointed the direction of Bunga Too. Candano went without looking back at his wife.

***

Olum and his sons crossed the Orwo Pii stream that spread between the forest and the village of Cet-Kana. Orach pulled Lamaro through the stream with a tight grip on her hands – her mouth was gagged with a piece of red cloth. He slipped on a rock and they both fell in the stream.

‘Coward. Why are your legs trembling?’ shouted his father.

‘I am not.’

‘Then pick her up. We are almost there. Not for long that land is going to be ours.’

Obuu, Olum’s second-born helped Orach and Lamaro up. They crossed the stream and entered the forest.

***

Not far away Candano picked up their trail when he found drops of blood on the grass.

‘This must be her,’ he whispered to himself when he finally found a footprint. He pulled a knife from the leather pocket and increased his pace humming his favorite song. Unable to hold it inside any longer, he broke out:

….ngat ma ogudu nyani nongo o’ero lweny

Ma ikoma wek obedi pe igud ba

Ma ikoma degi kolo pe icak ba

He crossed the Orwo Pii stream and heard a faint sharp cry in the forest.

Not far away the kidnappers in their rush had not seen the puff adder. It had bitten Komakech, the boy that followed Oneka in birth. Now the serpent raised its head with ferocious viciousness towards Olum but Oneka slashed its head from behind. Komakech dropped to the ground, convulsing vigorously as his body stiffened. Orach sobbed but his brother’s stiffened body could not resist the venom any longer. Breathing heavily, Olum told his sons that it was unusual for a snake to bite anyone from his family and that they would come back to bury Komakech. Then, he urged the others to hurry as they needed to get where they were going before nightfall.

The hyenas howled as the sun hid under a cloud and the forest became darker. They walked for another hour and then Olum told his sons “We shouldn’t go further ‘Twe laming pa Candano ni ikom agaba eno ni,’ Olum said and pointed at a Kituba tree. The boys tied Lamaro with agaba to the Kituba tree as they were told. Then, they heard rustling behind them and the breaking of twigs.

‘Go check who it is,’ Olum ordered Orach and Oneka. ‘If it is that godforsaken wretch make him pay for your brother’s death.’

Orach took one step after Oneka who was shaking with a slack grip on his knife. They saw three hyenas running off and Orach took a deep breath. Before he could fully exhale, his knife was grabbed from behind and he felt Candano’s muscular arms round his neck. Oneka waved his panga to the left and right forcing Candano to let go of Orach’s neck. Orach gasped for breath. Oneka swung his panga around aiming for Candano’s head but missed.

Reaching for his leather pocket on his back, Candano plucked an arrow and drove it through Oneka’s left leg. The boy fell calling out for his mother. Orach then screamed his lungs out when Candano stabbed his right leg.

‘Where is my daughter?’ Candano asked Oneka at knife point.

‘There’s a Kituba tree close by. Father and Obuu have her.’

***

Candano reached the Kituba tree and stopped at a distance. He circled it but Obuu saw him. Candano quickly lifted his bow and picked an arrow from his leather pocket. He jumped on the ant hill in front of him, aimed and shot Obuu’s right leg. He fell like an elephant wailing ‘Maa atoo’

‘Abaa … I am here,’ Lamaro cried on seeing her father.

Olum ran towards Candano before he could reach for the next arrow in his leather pocket and dived on him. They rolled over against a mahogany tree. Candano struggled to get up as Olum pinned him picking up an arrow in his hands.

‘Son of Moi, the land is mine’ Olum told Candano raising a broken arrow and thrusting it towards Candano’s heart but instead he pierced Candano’s right palm. Candano’s bow was meters away but his leather pocket was empty.

Olum tried to pull the arrow head out of Candano’s hand but the pain forced Candano to throw himself up on Olum with immense force and punch Olum’s face repeatedly with his left hand.

He stopped when Olum stopped struggling and dragged him to where his daughter was tied up. When he released her he lifted Olum and tied him up with agaba on the same Kituba tree that his daughter was tied to. He stuck a knife two feet away and told him, ‘Use that knife and cut your way out when you get the right motivation to life. Your life is in your hands. The land is mine,’ he said.

He turned to his daughter, ‘Can you walk?’ he asked.

‘I have bruises all over my feet.’

‘Come here,’ Candano said offering his shoulders.

Candano carried Lamaro out of the Bunga Too. He reached home after night fall. Ayaa was seated outside by the fire with some neighbors whom she had told about the incident. When Ayaa saw them, she screamed so hard.

‘She’s just weary,’ Candano told his wife as he took Lamaro inside his main hut. Ayaa cleaned her up and dressed the bruises in her feet with healing herbs.

The story spread like a wild fire in the village of Cet-Kana.

Olum buried his son Komakech.

‘Indeed you are unlucky,’ Olum cried patting Komakech’s grave after the burial. Komakech’s name meant, ‘I am unlucky.’

Olum’s wife cried a river of tears for Komakech and blamed Olum for the loss of their son because of his insatiable greed.

***

Two years passed. Olum never again disturbed Candano or anyone in Cet-Kana. The events in Bunga-Too stopped the frequent ridicule poured on them by Olum and his sons. Temceo never stopped telling the story of how the troublemaker of Cet-Kana had been immobilized. From that day Olum kept to himself and did not join the other men in the village even when there were celebrations.

Temceo never stopped repeating the story. On the days he could be found under the Mvule tree he would shout: ‘Brrrrr, dog poop and dog pee,’ holding his alcohol gourd close to his heart.

‘I would never dare a sleeping lion to a duel, not even a dying lion on a bush trap.’ He stood trying to get a balance. His eyes whirled like aerofoil. He shook his head with such an amount of energy as though he wanted it out of his body and sneezed.

‘Aiisshhhh! Not even a dying lion or else history will dawn on you like it has on my brother, Olum. Let it be known in the community of Cet-Kana,’ he continued with a voice louder than ever.

‘Let it be written in the book of history, that I, Temceo son of Olyec, a respectful and a respected husband and father was there when these things happened. Full stop!’