Reviewed by Beaven Tapureta

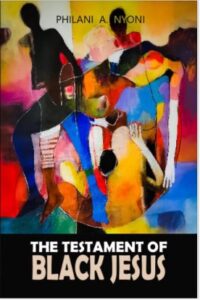

The Testament of Black Jesus (2024), an epic by the award-winning protest poet Philani Amadeus Nyoni, presents a black saviour who, according to the poet’s words, ‘rises to speak great and dangerous words’. The saviour has a responsibility thrust upon her by past events, to spread the legacy, good or bad, of men, women, and children who witnessed first-hand the collapse of African pride and democracy in an unnamed Southern African country.

A poetical carte du jour this collection is; and piercing are the words, as if cutting through a rocky fragment of an unwanted history, a part of history which the epic delves into to expose the stink and sting of human rights abuse, unchanging political landscape, economic failure and poverty.

As I wrote elsewhere, Nyoni belongs to a regime of “the Marechera-incarnates who, as they suffer the longing for their hero, have turned him into a demi-god”.

His latest book, The Testament of Black Jesus, is not far from the mark of Marecheranism, making him an explosive poet who refuses to accept or follow the common narrative. He subverts, or rather transgresses, the common religious and political thoughts.

His personae in the epic speak in a sharp lyricism that experimentally echoes that of the English poets such as John Milton who is remembered for his epic Paradise Lost which describes humanity’s fall from grace. The poet says that he chose the epic form after six years of digging into the classics of ‘the good old boys’, as he calls them: Homer, Dante, Milton, and others. However, Nyoni maintains his exceptional originality in diction, style, tone, and spirit.

The Testament of Black Jesus is divided into six cantos – ‘And She Passed In The Midst of Them’, ‘Immaculate Conception’, ‘Gipite’, ‘The Baptist’, ‘The Eucharist’, and ‘Sermon at the Fount’. And the poem ‘Crucifixion’ makes the epilogue.

‘And She Passed in the Midst of Them’ plunges the reader into a dramatic dialogue of ideas between a traditional patriarch and a woman who defends motherhood and accuses man for his

…wickedness that demands

Honour and higher station for nothing

But a twist of chance

Such disparaging language used by the man to refer to the woman as ‘simple mind of lesser sex, so soft as fodder!’ provokes feministic anger. Throughout the epic, there are voices of the two major women Nomazulu and Mkanyiselwa (The Enlightened One) who counter this negativity with strong vindication of motherhood and its natural leadership genius.

Mkanyiselwa, wise and outspoken, stands for African spiritual restoration. Her person resembles the African female revolutionary. She emerges from the Savannah dust and appears to her people who are ‘in waiting’ but for temporary relief in the form of government aid. She offers them a too-hard-to-swallow message of spiritual freedom, just as in the Bible Jesus Christ rendered complex teachings that contradicted tradition and law.

She dares speak of an unforgivable sin colonialism did to the beloved Africa, that is, the annihilation of its spirituality.

The god of your master cannot be your god

For a god that keeps any master above you

Is beholden to keep you lowly as the clod

Is Mkanyiselwa the Black Jesus? She has no honour in her own country. It confuses those whom she addresses, that as a woman she still dares to call herself a ‘simple man’ or ‘Son of Man’.

I am whatever you say I am

I am a simple man, just like you

I am he like rain is dew

The Son of Man came to seek and to serve the lost

The urgent need for physical satisfaction conflicts with the revolutionary spiritual message she brings them. Among those she is speaking to there is one called The Adversary who asks her:

What use is a fed spirit when the belly is rumbling?

They doubt her mental health, rule her words as blasphemous. Eventually, she is told to leave, and Nomazulu, the woman who had been with those in waiting, follows her – thus the two women form an unbreakable bond of sisterhood.

This epic, which draws from the recorded gospel of Jesus Christ and freely subverts it, will raise the roofs among Christians. This is apparent in the last canto ‘The Sermon on the Fount’ in which, for example, the popular Lord’s Prayer, the prayer that Christ gave his disciples in the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 6:9-13, begins in another form as follows:

Our Mother,

Who art an ebon’

Harlot be thy name,

Thy King done come

Thy will be done to death…

And The Beatitudes, the eight sayings of Jesus at the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount, are altered by the poet to become ‘beatitudes of power’, for example;

Blessed are the poor

For they shall inherit the dirt

Or

Blessed are the meek,

For they shall inherit a hole in the earth

Mkanyiselwa tells her history in the second canto ‘The Immaculate Conception’ which reverberates with emotional bitterness about a genocide that happens just when everyone thought Independence had manifested. Her mother, having been “cornered by a beast’, conceived her obviously as the genocide raged. It is a fact that many women are raped during times of war and their children are neglected. Describing the brutal way she was conceived, she says:

I am the scar that was given a name of love

But I did not fade

And so I was conceived,

Not from the love a man sang to the doves of the forest,

Not the love a woman sang to the hearth at sunset,

Not the peace of Independence and black conquest,

I was the child of the bayonet.

‘Gipite’, the shortest and third canto, portrays the plight of a single mother, the reader may guess it’s Mkanyiselwa’s mother, in a time of hunger, who is looking for gold, not the real gold, but it seems it’s a metaphor for the type of yellow maize that government imported some time back when Zimbabwe faced extreme hunger. Her fight for the survival of her child (Mkanyiselwa) is taken for granted by the government aid man who, instead of giving her “grains of gold to pound and nourish” her child, is but concerned with taking advantage of her. For example, unbeknown to him that he is serving a nation in need, the government aidman openly displays his selfish passion for her when he says:

Your limbs are spare, but your beauty’s rare

That is my fault, like this leap year.

I want to taste you, I dare say.

Mkanyiselwa’s mother resists the power that oppresses women, a quality she bequeaths her daughter. Just as her mother whose “spirit carried her more than her body”, Mkanyiselwa is spiritually mentored as shown in the fourth canto ‘The Baptist’ in which she receives the sacrament of wisdom from

The man of the mountain

Whose groin was covered in a loin skin

Who gurgled the brook and babbled the tongue of his ancestors

Possibly a medium, The Baptist describes in a satirical tone the mental strangulation that came with colonialism which stealthily abused the Bible to take away the spiritual dignity of the black people.

In this canto, as in the others, Nyoni tackles head-on the process used to control the African mind. But one may ask, is it the missionaries to blame or Jesus Christ about whom the colonialists hypocritically preached?

The Baptist vents his anger upon the colonial preachers of falsehood who “poured darkness on the black mind and called it illumination” while they stole the land. Now the black people, intellectually Westernized, no longer know their roots and The Baptist mocks them as a lost generation. For instance, he says:

You say I should be grateful I can read,

But I cannot translate the hieroglyphs or the wisdom of my fathers

Chronicling freedom or the riddle of the hunter …

Nyoni’s epic The Testament of Black Jesus carries the message of a radical return to the source of African pride. Although some Christians may find it hard to read and enjoy, its substance rings loud and clear: Africa must consider her history.

Nyoni’s previous works include the poetry collection with record-breaking sonnets and Philtrum (1st and 2nd editions). He has won various awards in and outside the region.