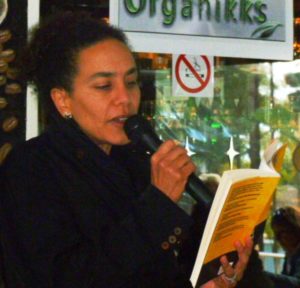

Sarah Ladipo Manyika was raised in Nigeria and has lived in Kenya, France, and England. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, and teaches literature at San Francisco State University. Her first novel, In Dependence, was published by Legend Press in London, Cassava Republic Press in Abuja and Weaver Press in Harare. Sarah sits on the boards of Hedgebrook and San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora. Last year, she was the Chair of Judges for the Etisalat Prize for Literature. She hosts the OZY video series, Write.

Sarah Ladipo Manyika was raised in Nigeria and has lived in Kenya, France, and England. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, and teaches literature at San Francisco State University. Her first novel, In Dependence, was published by Legend Press in London, Cassava Republic Press in Abuja and Weaver Press in Harare. Sarah sits on the boards of Hedgebrook and San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora. Last year, she was the Chair of Judges for the Etisalat Prize for Literature. She hosts the OZY video series, Write.

MANYIKA EXPLORES AGEING IN SECOND NOVEL

Reviewed by Beaven Tapureta

USA-based author Sarah Ladipo Manyika’s second novel Like a Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun (2016, Cassava Republic Press Abuja-London) is a courageous investigation into the joys and vagaries of age, and at the same time, a subtle unveiling of the racial battle running beneath multi-cultural American society.

Like A Mule Bringing Ice Cream to The Sun was officially launched in Harare (Zimbabwe) at the Organikks in July this year. The novel’s long poetic title is taken from a poem Donkey On by Mary Ruefle.

The story in this novel, told from the viewpoint of various characters, moves with alternating humor and seriousness while the reader inevitably falls in love with the protagonist Dr. Morayo Da Silva, a writer, avid reader and former wife of an ambassador.

Indeed, after reading Manyika’s novel, one would agree with award-winning Zimbabwean author No Violet Bulawayo who observed, “If ageing be a lamp, then Morayo, the protagonist, is a mesmerizing glow. Astute, sensual, funny and moving.”

Memories of No One Writes to the Colonel by Gabriel Garcia Marquez also hurtle back if one has read the story, not because there is anything similar that demands critical look between the two works but just the interesting fact that while the Colonel, waiting for days on end for his pension check, exclaims, “No one writes to me”, old Morayo in Like A Mule Bringing Ice Cream To The Sun has huge deliveries of mail at her doorstep every day, thus contrasting very well with the seeming solitude of the old colonel and his wife.

There is no solitude in Morayo’s life except when she is reflecting on her past but still she does look back with a sense of accomplishment despite having been betrayed by his diplomatic husband Caesar. She has a carefree spirit until she sustains a hip injury that confines her to a retirement home from which she wishes she could be free.

Hip fractures due to falls are said to be a common injury among old people and the incident in Morayo’s life rather strengthens her as much as it takes away the pleasures of her own apartment.

The consciousness of other characters is delivered through their own first person narrations. The author, with occasional twists of point of view, allows them to speak, thus reinforcing the theme and sub-themes of the story.

Although living in San Francisco, far from her home country Nigeria, the well-travelled Dr. Morayo finds in her wardrobe “the smell of Lagos markets still buried in the cotton…” and the smell “evokes the flamboyance and craziness of the megacity….” She is up to date with happenings in Nigeria!

As Morayo plans and looks forward to her 75th birthday, you can’t help liking the characters that celebrate Dr. Morayo’s personality, such as Dawud the Palestinian shop keeper or Sunshine the one who shows us, through certain small events, that Morayo is deeply and spiritually attached to her books. Then there is Sage, a homeless but striking character who feels that it is tough living in America. “It’s tough out here, and sometimes when I read about Africa, I don’t see America being better. It’s really a crying shame. A crying shame,” she says in one of her monologues.

Sage is an affable character. Although toughened by trying to fix her own broken life, she is a promising humanitarian. No wonder why, as the story comes to an end, she syncs well with Dr. Morayo whose charity is outstanding.

Dr. Morayo’s new life at the Retirement Home where she is being treated of the injury suggests, for the reader, new perspectives into American life. Toussaint, the chef at the Home, after learning that Morayo is from Nigeria, asks if Nigeria is racist like America.

We meet Reggie Bailey whose wife Pearl has a disease affecting her sanity and is being treated at the same Home. When Reggie sees Dr. Morayo at the Home, he is surprised and he thinks, “There are some people in life that one just never expects to see in a place like this, doing physical therapy.”

But the Home is strategically a setting the author uses to reveal Dr. Morayo’s and other aged people’s private longings. When Reggie, for instance, “dreams of being held. Of being touched. Of being desired again. Of being recognised….” the reader, at this point, may ask, will his longings bring her close to Dr. Morayo whom he admires? Will they fall in love?

Earlier in her apartment before the accident, she had the same longing for romance which left her fantasizing “for a suitable person with whom to enjoy this unexpected surge of feeling”.

In the end, however, conversations between Reggie and Dr. Morayo get sensational and poetical as the space between them is occupied by a book in which scribbled is a poem the doctor once read for Reggie’s wife.

Sunshine, another character, comes into Dr. Morayo’s life at a time when she is sent to the Home to recover and Sunshine’s part reveals another aspect of the Doctor’s life. For instance, certain fake charities were taking advantage of Morayo’s wealth. When Sunshine appoints a helper to clean Morayo’s flat, the helper does something that hurts the devoted reader in Morayo – he throws away some of her precious books and this leads to outburst of anger!

And on her final return to her home, Morayo isn’t pleased by the new arrangement of her books. “The first thing I looked for were my books. I’d been dreading this and sure enough, just glancing around the apartment, my heart sank. The only books I could see were those on the shelves and they were so neatly arranged that it looked like my apartment was being staged, as though someone was getting ready to sell it,” she says upon arrival.

When she wildly drives away from her apartment, leaving behind Sunshine and the occupational therapists who had accompanied her from the Home, she meets Sage along the way and it is not just a meeting but some ‘return’ to freedom which both women have been looking for. Sage, a scavenger, is reading the books she picked from the dumpsite, books the Doctor knows belong to her personal library but she doesn’t show it.

Manyika’s language has shifted from the ‘serious’ in her first novel In Dependence to the colloquial in Like A Mule Bringing Ice Cream to the Sun yet she skillfully handles the momentum of her stories with a profound dedication to detail.

About the Reviewer

Beaven Tapureta is the founding Director of Win Zimbabwe, an organisation that networks Zimbabwean writers through the internet and through workshops and readings. He was one of the key staffers at Budding Writers Association of Zimbabwe (BWAZ) when it folded a decade ago. Tapureta is a trained journalist.

Beaven Tapureta is the founding Director of Win Zimbabwe, an organisation that networks Zimbabwean writers through the internet and through workshops and readings. He was one of the key staffers at Budding Writers Association of Zimbabwe (BWAZ) when it folded a decade ago. Tapureta is a trained journalist.