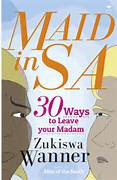

Zukiswa Wanner has written a deceptively simple book. If you have read The Madams (her first) and Men of the South (short-listed for Commonwealth Best Book 2010), you may have a few hints as to the setting of the book. Zukiswa concerns herself with South Africa. The New South Africa. This time, she is going deeper into the relationships between madams and their maids. Remember the protagonist of The Madams who hired for herself a white maid? That fact drove the plot of that novel, and just before we start reading Maid in SA, Zukiswa tells us that she ‘is still looking for her white helper – the cleaning, cooking and homework type.’ If you still doubted that writers do not envy their characters, doubt no more. Zukiswa envies the main character of The Madams.

Zukiswa Wanner has written a deceptively simple book. If you have read The Madams (her first) and Men of the South (short-listed for Commonwealth Best Book 2010), you may have a few hints as to the setting of the book. Zukiswa concerns herself with South Africa. The New South Africa. This time, she is going deeper into the relationships between madams and their maids. Remember the protagonist of The Madams who hired for herself a white maid? That fact drove the plot of that novel, and just before we start reading Maid in SA, Zukiswa tells us that she ‘is still looking for her white helper – the cleaning, cooking and homework type.’ If you still doubted that writers do not envy their characters, doubt no more. Zukiswa envies the main character of The Madams.

Maid in SA is classic humour. So many things to laugh loud about. But before you finish your loud laugh, you will start to see that what you are laughing about is actually a reality. That well, we can laugh about this reality for now, but shouldn’t we also do something about it? I think I take things too seriously. Someone accused me of this recently on Facebook, so here is the confession. I do not think Maid in SA is just a humour book. As the blurb says, the book is as serious as the security guards in gated communities. I want to add that it is more serious than those intellectuals in some ivory towers busy denying the existence of classes and real exploitation of some people by others – the masses as the exploiters derisively call them.

To continue with my confessions, and disclaimers; I am not South African, and have not lived in South Africa beyond two weeks. So, I come to the book as an outsider. I already feel that I am going to eavesdrop on South African life and conversations as I open the book. The title is after all ‘Maid in SA’, not Maid in Uganda, nor Maid in Tanzania. (I think I am getting obsessed with Tanzania, the same way South Africa is obsessed with Zimbabwe, or is it the other way round?) Let us forget all this, a few pages in the book and you no longer feel an outsider. You become the maid in these households, and the madam in some places, or the misbehaving child bribing the maid after the latter gets herself high on marijuana-ed cookies.

The book lays bare South African society, even though the title may create an impression that it only addresses maids and their madams. Through maids and their madams, Zukiswa makes very eloquent observations about South African society. Thanks to the book, what I have always said (on those very many Facebook rants) is confirmed – Class transcends race. The book tells us that the rich, super-rich Black Madam is not a black madam, she is a rich madam, in the league of old white South African money. Zukiswa categorises this class of madams into the noveau rich and old money. Then come the Indian madams, classified further as the conservative and the liberal middle class.

When it comes to the African madams, Zukiswa contends that there are no poor African madams. There is only one type of Black Madam. The middle class African madam. She takes her time to describe the relationship between the maid and the single African madam and the married African madam. And then she hops onto the White madams. We learn that poor White madams, unlike their fellow poverty-stricken counterparts in the African club, must have maids, even when they can’t afford. There are so many laugh-out-loud moments, but also very reflective passages in this particular part of the book. There is BEE in the mix (Black Economic Empowerment) and what the poor white madams think of it and of course their preference for Mandela in speaking about Zuma and Mbeki. The rainbowness of South Africa is simultaneously attacked and defended. The middle class white madam who wants her maid to support Hellen Zille’s DA and claims to have black friends who never visit is also dissected, in the real sense of the word. This Madam and her husband end up relocating from South Africa to England, Australia and other places when shit hits the fan.

Zukiswa does not just list ways in which maids leave their madams, she also dedicates a cool thirty pages of the a hundred page-count of the book, to guiding madams, reminding them of how their maids left and predicting how they will leave. Zukiswa is elaborate. She has notes on the city helper, the rural helper, the Zimbabwean helper, the Mosotho helper and my best of all, the Malawian male helper.

I was deceived into thinking that Zukiswa had written a self-help book, by the title. She, at a Writivism 2013 workshop in Kampala derided self-help books and cracked our ribs when she declared that they only help the writer, because money is earned when buyers invest their hope in the book. Zukiswa must be making a point against the self-help genre. I am speculating here, because the title does not live up to its self-help promise. This is not even mere humour. There is a lot of humour, but this is a very political book. But what on earth is not political anyway? I am now ready for Mohsin Hamid’s own self-help book. I think I love this type of self-help that is not self-help. I love Maid in SA. There should be more books like this.

Bwesigye teaches Law at St. Augustine International University and Human Rights at Makerere in Kampala. His work has appeared in the Kalahari Review, African Roar, Saraba Magazine, Uganda Modern Literary Digest, The New Black Magazine and in Ugandan newspapers.

Bwesigye teaches Law at St. Augustine International University and Human Rights at Makerere in Kampala. His work has appeared in the Kalahari Review, African Roar, Saraba Magazine, Uganda Modern Literary Digest, The New Black Magazine and in Ugandan newspapers.

1 comment for “Zukiswa Wanner’s “Maid in SA”, Reviewed by Brian Bwesigye”