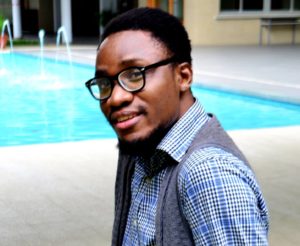

Munachim Amah (Nigeria) explores family, loss, and gender through his writing. He is an alumnus of the 2016 Farafina Trust Creative Writing Workshop and has short fiction and creative non-fiction published in Saraba Magazine, African Writer, Kalahari Review, and forthcoming in Bakwa Magazine.

Munachim Amah (Nigeria) explores family, loss, and gender through his writing. He is an alumnus of the 2016 Farafina Trust Creative Writing Workshop and has short fiction and creative non-fiction published in Saraba Magazine, African Writer, Kalahari Review, and forthcoming in Bakwa Magazine.

Stolen Pieces

Class: Primary 6

Age: 9

Gender: Boy

My cousin, Ikenna. He was fifteen; I was nine. In 2001, mother invited him for a long vacation at our three-bedroomed apartment in Awka, and while we were playing husband and wife in my room, he threw his huge arms around my neck and asked me to kiss him. Suddenly, I couldn’t think anymore. I couldn’t breathe anymore. My head was swollen. My legs felt heavy. Please, he said, bringing his mouth to my face in slow motion. That was when I stepped back. I ran to the bathroom and bolted the door; my hands were trembling.

_____________________

Class: Secondary School, Class 2

Age: 11

Gender: Boy

There was a handsome boy called Ifediba in my school. Ifediba could smile at you and you would throw yourself at him and beg him to do whatever he pleased with you; I’m not even kidding. Boy was fine: cute dimples, fine set of teeth, neat afro (and boy could take care of his hair!). He was our hostel prefect. Everybody liked him because he was good-natured and calm and not like the other senior students who shouted at us all the time. Me, I admired him from a distance. One day, Ifediba came to my corner and asked me to be his “boy”. He said it so casually, the way a senior student would call you and send you to the canteen to buy Limca for him, and when I said nothing, he walked away.

In those days, being a senior’s boy was a privilege. If you were a senior’s boy, you would run small errands for him and enjoy certain immunities like exemption from manual labour and freedom from bullying seniors. If the senior liked you well enough, you would have the key to his cupboard, and that meant access to his provisions, to everything, and he might even help you with academic work. So, yes, to be a senior’s boy was a really big thing. But I wasn’t sure what I wanted. I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be anybody’s boy.

The next day, however, I found myself in Ifediba’s room (hostel prefects had special dorm rooms). I rubbed dusting powder on his back while he tried to sleep. The day after that, I read stories to him. The day after the day after, I sang lullabies to him. Each time, he kept a steady gaze on my lips and on my face, and my heart thumped in my chest, until he snored away.

Three days after Ifediba came to my corner to ask me to be his boy, he kissed me. I was rubbing dusting powder on his back in one minute and in the next minute he turned around, lifted himself gently from the bed and found my lips. I couldn’t breathe. He was looking into my eyes, kissing me while he did so, and all I could think of was his handsome face and his slender fingers on my face. Go to your corner and wait for me, he said, pulling away. I said okay and got up, trying so hard to stop myself from falling. By the time I got to my bed, I was trembling with anticipation.

Ifediba did not come to me.

A few days later, I saw him under the dogonyaro tree in front of the girls’ hostel. Our assistant social prefect, the cheeky one, was sitting on his lap and giggling like a sheep. I said, What? What is this nonsense I’m seeing? What is this rubbish? This girl was giggling on Ifediba’s lap and Ifediba was whispering something into her ears and they looked so happy, so assured. They were not even hiding. Any teacher could easily be walking by and see them there, but did they look like they cared? No.

I did not say anything. I just went to Ifediba’s dorm room and dropped the keys to his cupboard on his bed and left. I told myself I would not do anything for him again. The cheeky girl should come and be his boy.

Ifediba did not call me to his room again after that day. He did not ask me why I returned his keys. A few months later, he graduated and left school. Not a word from him, no message, nothing. I kept hoping he would come back one day and tell me that it was all a mistake, that he had realized the error of his ways, but I was clearly waiting for a dead man to come back to life. Nothing happened.

Eventually, my hope thinned out and I gathered whatever was left of me and moved on.

_____________________

Class: Secondary School, Class 4

Age: 13

Gender: Not sure

Nnamdi zoomed into my life like an ambitious rain in the middle of dry season; he literally did not let me rest. We were classmates, and all my classmates avoided me because they judged me a snob just because I did not fancy throwing my mouth into every conversation that passed by. But not Nnamdi. Nnamdi did not leave me alone. He pursued me round the whole school as if I was a trophy. He said I must be his friend whether I liked it or not. I refused to look at him, and this boy went to my best friend, Ebube. This boy lay down in front of Ebube, with his sparkling white shirt and khaki shorts, and begged Ebube to beg me to please accept him as my friend.

And that was how Ebube came to me with questions. Why don’t you like Nnamdi? Why don’t you like this boy that likes you so much?

He said Nnamdi lay on the floor, in front of our classmates, begging him to please talk to me, to please tell me to give him one small chance, one tiny chance, and I imagined Nnamdi on the concrete floor of our hostel, his white shirt and short stained with brown dust.

Nnamdi is too loud biko, I said. Somebody that cannot keep his mouth shut for one minute, is that who you want me to be friends with?

Ebube laughed and went and told Nnamdi what I said, and the next thing I knew, Nnamdi came to me, in my corner, promising heaven and earth if I agreed to become his friend, swearing to God that he would change. I said, Okay, let’s see.

Let’s see and we became buddies. Let’s see and Nnamdi started bombarding me with gifts – NASCO biscuits, sachet ice-creams, Ribena juice, expensive body sprays. I said, But Nnamdi, is this not too much? Nnamdi said, Nothing will ever be too much for you, Nkem. He called me Nkem, mine, as though he meant it literally and not as an abridged version of my name.

This boy did not stop there. He insisted on washing my school uniforms and day clothes and stockings, insisted on fetching my bathing water from the school tank every day, insisted on doing my class projects. Ebube said the love was too much. I did not know what to reply him.

On Valentine’s Day, Nnamdi bought me a nice-smelling handkerchief and a Valentine’s card. There was a message on the card: “Nkem, I love you.” I read it and immediately burst into laughter. It definitely was not Nnamdi’s handwriting. Someone must have written the words for him. Who did not know that Nnamdi’s handwriting was terrible? Who did not know that his handwriting was confusion to the power of hundred? At first, he did not know why I was laughing. He thought maybe I did not like the gift and was amused by it. But then seeing that I won’t stop laughing, he asked why I was laughing, and that was when I held out the card to him and said, Nnamdi, gwa m eziokwu, whose handwriting is this? He hissed and rolled his eyes and hissed again and said, Nkem, you are stupid o. Do you know? Ibu ezigbo onye ala. Then, he gave me another hiss and walked away. I laughed and laughed and laughed that day. I just could not stop laughing.

I started sleeping on Nnamdi’s bed, on the 6-inch spring mattress in his corner. I found comfort and joy there. I found laughter with him, and it baffled me how someone I had dismissed at first became the most important person in my life. On nights when the heat inside the hostel became unbearable, we carried his mattress outside the hostel and slept under the local fruit tree. Sometimes, while pretending to be asleep, he would slip his hands into my shorts, and I, also pretending, would snuggle into his arms. One day, Nnamdi said to me, maybe we will get married to each other someday, Nkem. Maybe. I called his name and said, Nnamdi, ka a na-ejegodi. Let’s see what tomorrow holds.

Two months later, a rumour spread through our school. I heard from someone who heard from someone who heard from someone that Nnamdi was dating one of our classmates and that, in fact, she was pregnant. Could it be my Nnamdi? I thought as I ran to the hostel. Could it really be my Nnamdi? When I got to his corner, I saw him throwing things from his cupboard into his big iron box. Nnamdi, I said, Nnamdi, gwam eziokwu. He did not even stop to look at me. Is this thing I hear true? He did not say yes. He did not say no. His hands kept travelling from the cupboard to his box. He was sweating profusely, and avoiding my eyes. And so, I concluded for myself that Nnamdi must have been doing it with the girl, right under my nose.

Nobody saw him after that day.

We had been “friends” for three and a half academic terms.

_____________________

Class: Year 2, Department of Mass Communication, University of Nigeria, Nsukka

Age: 18

Gender: Boy

Nwando came into my story like a fairy. When you imagine Nwando, think of a collected person. Think of a young girl wearing dull-looking, loose-fitting clothes, carrying her hair all natural and kinky, walking to school with earphones plugged into her ears and paying no attention to the world. Think of a girl completely immersed in her own world, giving no damn about who slept with who or who went for what party. When you think these things, imagine Nwando.

This girl, Nwando, started coming to me with questions. She would stand before my desk in class and peer at me through her spectacles, her notebook and pen in her hand, and she would ask, Nkemdilim, can you please explain the Poynter Pyramid? Nkemdilim, what do you think Professor Okunna wants from us in this assignment? Nkemdilim, can you please elaborate on the concept of technological determinism? She talked to only me in class, only me, and this made me feel very happy and very special.

The day she asked for my phone number and I asked for hers in return, we talked for over three hours. We talked and talked and talked until there was nothing to talk about. It was as if someone said: if you people stop talking, you will die. We had both lost our fathers: hers from a stroke; mine from oesophageal cancer. Both our mothers worked for the government: hers as a civil servant in the State Ministry of Health; mine as a secondary school teacher. Both of us adored Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: she had applied to her workshop but did not get in; I hadn’t even tried. The list of commonalities just went on and on.

We were walking to the bus stop from the lecture hall one day when she remarked that I was a nice guy and that she liked me very much. I wasn’t sure what to say. She smiled, I smiled, and we continued walking. Suddenly, something came over me and I asked, out of the blue, if she wanted to be my girlfriend. The question must have surprised her because she stopped walking, and I stopped walking too, and I was even all the more surprised at myself for asking her that question. It’s not that I was ready to love again or tired of being alone. I just couldn’t help myself with Nwando. Every time I looked at her, something told me we belonged together, forever, and how else would that happen if she didn’t become my girlfriend?

Nwando stared at me for a very long time. Then she said yes.

The next day we went to a Mama Put close to school gate and ate roasted plantain and beans with uziza. Occasionally, she glanced at me; sometimes I held her gaze, sometimes I looked outside the shed to avoid her eyes. Are you shy? she asked. I smiled. Later, when the mama in charge of the Mama Put came to collect money for the food, Nwando waved my hand away and brought out 500 naira from her purse. I was puzzled. I was supposed to pay. I was the guy. Real guys paid the bills and took care of their girls. Don’t bother, she said, holding my hand as we stood up.

We did it in her room a few weeks later, after trying so hard to quell our raging emotions. Nwando tried to make everything seem normal. She led me. When I rolled off her and she asked, Did you come? and I did not know what to say because I did not know what exactly “come” meant, she looked away. She grabbed the bed sheet and flung it across her body, as though she needed to shield her body from something, as though she was fighting some monster that suddenly appeared in the room.

When Nwando did not say a word to me again, when she did not stand up to walk me to the gate when I was leaving, when she started avoiding me and refused to answer my calls and refused to respond to my constant what-is-happening? messages, when I did not see the excitement that had been in her eyes when it all started, I did not need a soothsayer to tell me that it was over. I picked up what was left of me and, again, drifted off.

_____________________

Class: Year 3, Department of Mass Communication, University of Nigeria, Nsukka

Age: 19

Gender: Man/Not Sure

Father Albert slipped into my life at a time when I was searching for something bigger than faith. I had gone to Mass that day, and as I sat in the congregation listening to Father Albert’s sermon, listening to the rise and fall of his voice as it rang out like a metal gong, like a sweet melody rising up to heaven, I wondered how people managed to concentrate on his sermon. By the time the Mass ended, and Father Albert and his retinue of altar servers marched into the sacristy, I knew I would return to the Chaplaincy again.

It was a Tuesday morning when I went to see Father Albert in his office. I did not mind waiting in a long queue for over two hours and watching the overzealous catechist prance around in an effort to assert his authority. I did not mind his loud, annoying voice. You do not make noise here o, he told one woman that was talking to a pregnant lady beside her, and for a moment I wanted to tell him to just shut up. Did he think this was heaven?

Eventually, the catechist announced my name, and I did not know when I made the sign of the cross. What a relief to be rid of the lousy man. Once inside Father Albert’s small, air-conditioned office, I stood by the door to take in everything: Father Albert bent over a book, an almanac hanging on the wall, a white table, three white chairs, piles of books on Catholicism and Faith on the table, a glowing crucifix. Father Albert raised his head from the big book he was reading and asked me to sit, and as I sank into the chair, directly opposite him, it felt as though Jesus was truly there, truly present. Maybe Jesus would help me, I thought. Maybe Jesus had all the answers to my questions.

He asked why I came to see him, and I told him I wasn’t sure. I told him I hadn’t been to confession after my First Holy Communion when I was eight, hadn’t been receiving the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. I told him I no longer believed in the Christian God. I believe there’s a force behind creation, I said, but I don’t think it’s anything like what Christians have set up for themselves. I told him I did not understand myself either, had never understood myself, particularly my sexuality, and that this was a source of great worry to me. I did not stop talking until I was crying, until I could no longer hold back my tears.

God is a mystery, he said. We may try all we can but we will never fully comprehend him or his actions. He is always calling us, always willing that we draw nearer to him. His voice alone was therapeutic. Father Albert did not exactly clear my doubts that day, but in the days that followed, I wore his words around me like a second skin. I could tell that he made an effort to understand and not outrightly condemn me like other priests in the past had done, and this made me love him even more.

Every Sunday after Mass, I rushed to the back of the sacristy to greet him, and smiling, he would hold my hands and ask how I was doing. The Lord is good, he would say in his sing-song manner. All the time, I would respond.

On one of those solemn Sundays, I went to greet him as usual after Mass and he asked me to stop by the parish house for lunch. It was when I went to the parish house that I saw it in his eyes: the affection, soft and tender, lurking behind the veil of caution. In some ways, this excited me. I imagined myself the subject of interest of this powerful person, this priest leading a large congregation of young people like me, and just thinking about it made me feel worthy, made me believe that, at least, there was something left of me worthy of admiration. But I was not ready to be the reason why a priest was derailed from his preordained path, so I packed up and headed out again.

Father Albert gave up after several attempts to reach me.

_____________________

Class: Graduate, Ex National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) member, Working-class graduate

Age: 24

Gender: Not Sure (Sometimes man, sometimes woman)

If, at 24, you have not fallen in and out of at least five relationships, you have not doubted your entire existence, you have not questioned God and life and death and after-life, maybe you have not started living, maybe there’s something wrong with you. Because at 24, I was drifting. I was paddling my way through life’s deep oceans. I was searching for answers everywhere, looking for pieces of me in people’s faces and stories, in towns and cities and villages, in the darkness and silence and bleakness of the night.

And that was how Udokasi waltzed into my life like a star slowly making its way across a dark sky on a quiet night. It was his name that I first took a special liking to: Udokasi, peace is the greatest.

Then, his charming smile.

Then, his gentleness.

Our friendship started on Facebook but eventually blossomed out of it.

On the day we first met, I remember thinking, as we sat in front of the pond at Freedom Park watching the noisy ducks, that the conversation we had that afternoon was the most honest conversation I’d ever had, that I’d never been freer in my entire life.

I had the urge to bare myself completely to him, to tell him everything about me. I wanted to see him every day. I wanted him to hold my hand, to just hold it and place it on his chest so that I could feel his heartbeat and let the moment wash over me. I wanted, more than anything, to share my life with him.

And then, he reached for my hand and held it and, as if he knew what I was thinking, asked me to look at him, and I did, and what he said next broke me.

I think it’s okay to love anyone, he said. I care about you. But I’m going to marry a woman some day. You will too, won’t you?

It felt like someone was cutting my chest open, tearing me apart. But I did not say anything. For a long time, neither of us moved, and it was as if the world was quiet, dead. He was still holding my hand. In the pond, two ducks started fighting. They pecked at each other and made throaty sounds, dashing back and forth and splashing water around. After some time, they drifted apart, each paddling away in an opposite direction, and the world became silent again.

It’s the right thing to do, he said, picking up from where he stopped.

I wanted him to shut up. His words made my skin itch. I kept my gaze on the pond, but I could feel his eyes on my face, and I wanted so badly to stick a finger into one of his eyes and watch him wince in pain. Stupid, I thought. You’re so stupid.

Of course marriage crossed my mind. Of course marriage was a possibility, if not a responsibility. But my lines were not as clearly drawn as his. Why did he not see that? Why did he not see that my boundaries left room for possibilities, for us? Why was he strangling something that hadn’t even come alive?

He said we should be friends, said we should not sentence ourselves by committing our lives to something we did not yet fully comprehend. It did not invalidate how he felt about me, he assured me. I said okay, all the while struggling not to cry in front of this man from whom I wanted something more than friendship. It was on my bed, later that day, that I let it all out. I cried and cried and cried.

Four months later, communication between us soured. When we talked, which was once in a while, an irritating silence hung over us. Our conversations became shallow. I made faces even when I tried so hard not to and looked for reasons to stay away from the phone.

One day, something loosened in my head and I decided I’d had enough. It was time to move on. This time, I made sure not to leave any piece of me behind. I picked up everything. I had become a tiny little bird, moving and perching, looking for some safe place where I could at least rest and find something to eat.