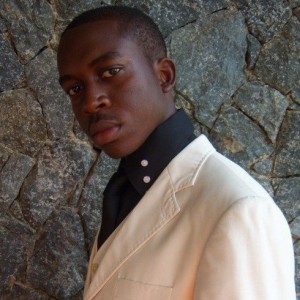

Nkiacha Atemnkeng is a young Cameroonian writer and blogger at nkiachaatemnkeng.blogspot.com. His short story “Football without a ball” was shortlisted for the 2013 Mardibooks short story competition in London. He was also a finalist for the month of October 2013 at the Africa Book Club with his children’s story, “The Golden Baobab Tree” hence was published online at africabookclub.com and is forthcoming in the anthology. Nkiacha has also been published online by malawiwrite.org, www.thenewblackmagazine.com and munyori.org. He has recently been invited to the 2014 Caine Prize Writers Workshop in Zimbabwe. A holder of a Curriculum Studies and Biology degree, he works as a Swissport customer service agent at the Douala International Airport in Cameroon.

Nkiacha Atemnkeng is a young Cameroonian writer and blogger at nkiachaatemnkeng.blogspot.com. His short story “Football without a ball” was shortlisted for the 2013 Mardibooks short story competition in London. He was also a finalist for the month of October 2013 at the Africa Book Club with his children’s story, “The Golden Baobab Tree” hence was published online at africabookclub.com and is forthcoming in the anthology. Nkiacha has also been published online by malawiwrite.org, www.thenewblackmagazine.com and munyori.org. He has recently been invited to the 2014 Caine Prize Writers Workshop in Zimbabwe. A holder of a Curriculum Studies and Biology degree, he works as a Swissport customer service agent at the Douala International Airport in Cameroon.

There is a saying, “If you want to know a country, read its writers.” So for me the anchor of We Need New Names will always be the last paragraph of page 193 which ends overleaf.

“There are three homes inside Mother’s and Aunt Fostalina’s heads: home before independence, before I was born, when black people and white people were fighting over the country. Home after independence, when black people won the country. And then the home of things falling apart, which made Aunt Fostalina leave and come here. Home one, home two, and home three. There are four homes inside Mother of Bones’ head: home before the white people came to steal the country, and a king ruled; home when the white people came to steal the country and then there was war; home when black people got our stolen country back after independence; and then the home of now. Home one, home two, home three, home four. When somebody talks about home, you have to listen carefully so you know exactly which one the person is referring to.”

I will go with Mother of Bones. Her Home one was a land called Great Zimbabwe ruled by black kings. Her Home two was called Southern Rhodesia, stolen by a white man, Cecil John Rhodes and his proxies (the colony was even named after him). Then there was war spearheaded by the secretary general of ZANU called Robert Mugabe and others like Edgar Tekere who managed to yank the country back from Ian Smith’s claws in the Rhodesian bush war from bases in Mozambique. Her Home three is the country now known as Zimbabwe, currently under the leadership of Robert Mugabe who won the general elections in 1980 and became Prime minister on Zimbabwe’s independence in April 1980. Contrary to what many people think, it was a thriving peaceful country after independence, the land where milk and honey flowed with good health and education policies until something snapped. Mother of Bones’ Home Four is that snapping Zimbabwe of the lost decade (2000 to 2010), the period when the economy shrunk largely due to Robert Mugabe’s land reforms. It is that Zimbabwean decade of things falling apart. So you have to be careful when citing the “country” of “We Need New Names.” It is actually the “Achebean-era-Zimbabwe,” only. That is, Home Four with respect to Mother of Bones and Home Three with respect to Mother. Even though the novel is set in an unnamed country, to me it is clearly Zimbabwe. A bunch of all these also happened in my country, Cameroon; from the pre-independence struggle in the late fifties, to independence in 1960, to the economic boom of the seventies, the stagnation of the eighties and economic crisis and political turmoil of the early nineties which led to the devaluation of our currency, the CFA Franc.

NoViolet’s debut novel parallels the media narrative of that lost decade era which peaked in 2008 perfectly. I remember following events in Zimbabwe from the news and this book is a wonderful evocation of all I heard, saw and so much more. (Well, except the juicy guavas). So it’s a blend of reality and imagination. There were media reports about hectares of farmland being seized from white farmers and handed over to black farmers, homes seized and others destroyed. I heard of galloping inflation, hunger, empty store shelves, rigged elections, violence as a result of that, incarceration and torture of MDC opposition leaders and political activists, some to the point of death, fed up Zimbabweans running away across the border into South Africa, a few knee deep across a bridgeless, crocodile-infested dangerous river, fed up Zimbabweans emigrating to America, emigrating to Europe, emigrating to Asia in droves and droves and droves.

However, not just anybody can perform such a no-nonsense task of chronicling all that and more into a heartfelt story that will charm thousands of readers around the world from Armenia to Zambia, New Zealand to Iceland, Cape to Cairo and India to Indiana. Not just anybody can spur the Man Booker Prize judges to colourfully and majestically drape such a novel especially a debut one with their shortlist flag. It takes someone with real literary genius. But she can do it like Barack Obama, that debut novelist from Zimbabwe called NoViolet Bulawayo who exploded onto the world literary scene in May 2013 like a fission bomb with her stunningly crafted novel. NoViolet Bulawayo is a new wordsmith who smolders red hot words of prose poetry into a finely chiseled arrow and firmly pierces your heart like Cupid, such that you can do nothing else but fall in love with her banging writing even if you may not like this her debut novel. She’s simply a reincarnation of ancient itinerant storytellers and the best traditional bards, period.

She wrote beautiful poetic prose with a lyrical feel to it such that her writing sings as if she’s playing symphonies on a lyre. It is fierce, feral, unsentimental prose written in the first person narrative and child’s eyes of the protagonist, Darling. NoViolet uses simple language and her jokester voice, her funny and playful voice to give dimension to and shape the world of six children: Darling, Bastard, Godknows, Chipo, Sbho and Stina who live a life some people cannot even begin to imagine, very reminiscent of the refugee children in E.C Osundu’s 2009 Caine prize winning short story, “Waiting.” The novel starts with a Caine Prize winning short story itself, her 2011 Caine Prize winning short story, “Hitting Budapest” which is actually one of my favourite short stories. But it’s a slightly reworked “Hitting Budapest,” (I read it 11 times in 2011 and spotted all the new lines in this novel.) The novel is set in a shanty town, a kaka neighbourhood called…oh my God! Paradise! What a paradox! But the paradise is not nice oh! The paradise is a sprawling suburb of hell. Bulawayo’s inferno ghetto echoes with sounds of despair, reverberations of people living without any hopeful hope triggered by the repressive rule of resident president, Robert Mugabe, (Africanist stance liberation hero or Zimbabwean economy Berlin wall disintegration zero as you like.) It is a dirty smelly place full of thousands of tin shacks and no real houses.

Extreme hunger prompts the six urchins to go and steal and stuff guavas in their famished tummies in a swanky neighbourhood called Budapest. The Hungarian capital! I’m thinking she should have named the place Miami or something, since it’s a really prominent suburb with chic beautiful houses. Their eleven-year-old friend, Chipo is pregnant for her grandfather! The children stumble upon a corpse and steal the dead woman’s shoes to go and buy bread! Darling pinches a baby so she can cry in church and she’s contented about it. The children poignantly attempt a futile abortion on Chipo. It’s like every dark thing happening is normalcy to them. But more than anything, life is a game. Just like other children, they play many games; Country game, Find Bin Laden game, Funeral game in “For Real,” Adult game in “Blak Power,” since they cannot go to school, since their teachers have all left, since their homes have all been destroyed, since there’s nothing else to do than to play and eat guavas to constipate themselves and drive away hunger. Their fathers have left for greener pastures in South Africa and elsewhere. And Darling’s father returns with AIDS instead of the goodies. Elections fail and the men return to their disillusioned lives. Men are clowns and dogs in this book; a man who impregnates his granddaughter, a false prosperity-preaching prophet called Prophet Revelations Bitchington Mborro, a senselessly verbose security guard, an AIDS-ravaged father, barbaric men looting from houses and writing on a wall with excrement, a mentally deranged old man called Tshaka Zulu.

Darling experiences all these horrors in her ghetto with childlike naivety but she has a deep sense of hope. “I’m going to America to live with my aunt Fostalina, it won’t be long, you’ll see.” She has a utopian view of America and doesn’t pause to think of the country’s own challenges as she dreams of it. Darling actually makes it there and is amazed by the variety of choice and food. But she also collides headfirst with America’s own problems and grapples with them a lot in silence as the writer continues to deepen and darken her world; the dysfunctional society, her illegal status, crime, American accent barrier, her estranged mannerisms, her repugnance for pop culture etc. So this also makes it a novel about emigration and the problems that also come with the illegal status of some Africans. Bulawayo skyrockets on the issue in a heartfelt chapter titled “How they lived”. It can make you cry. All these cause Darling to miss home and her friends a lot but she equally feels detached and somewhat snobbish and cold to them on the phone. The cultural dislocation and dilemma creates a gaping rift in her mind as she reaches adolescence, to the extent that she doesn’t even call her own mother, which brings to mind many Africans in the diaspora. She inherits habits quintessential to many American teenagers like the American accent, cruising as a group in town with the car of her friend’s mother which they drive without her knowledge, watching pornography online and texting. Bulawayo’s literary techie exploits; texting, skype conversations and facebooking in the novel contributed in making it a very contemporary book and all the more impressive because it was done in a novel written by an African which was a first for me.

There is the utmost conflict in the book between Chipo and Darling when the former accuses the latter of becoming Americanized and abandoning their country which she pretends to call home. The accusation angers Darling to the point that she hurls the computer to the wall. There’s also conflict between Darling and Aunt Fostalina over career choice. There is mind conflict between Aunt Fostalina and her husband, Uncle Kojo, over the Zimbabwean president, Robert Mugabe. Their marriage is also collapsing rapidly. From Aunt Fostalina’s actions, I get the impression she considers him to be a crumbled economy zero and Uncle Kojo openly declares him an African statesman hero. In my opinion, the title of the novel stems from the debate of that Mugabe longevity issue even though the phrase “we need new names” comes up only when the children are trying to choose Doctor names during their perennial playing. Here is Bulawayo’s opinion during an interview, “I feel we need a constant injection of new ideas, as in new personalities. It makes any space richer…When something is not working, you need to change it. So we need really a new breed, a new culture of politics to carry us to where we need to be.” So that summarizes We Need New Names, which ends with very little or no conflict resolution.

There are countless themes in the book; poverty, stealing, kids play, Religion, false prophecy, politics, AIDS, destruction, death, emigration, cultural dislocation, conflict, longing, mental dysfunction, infidelity, illegality, alcohol addiction just to mention some of them. The novel is an episodic plotted one with each of the eighteen named chapters spewing forth pages and pages of something unpredictable, new, poignant but generally funny like eighteen episodes of the family series, “Fresh Prince of Bel Air.” Each successive chapter presented a new story that simultaneously enchanted and piqued my curiosity. The book intentionally wanders about like Early man looking for fruits as nutritional fulfillment –guavas, stumbling on a ‘wild animal’ –a corpse dangling from a tree, six cubs playing constantly –(Country game, Find Bin Laden game), humans finding steel to make fire –wire used to attempt abortion on Chipo, lightning –flash of camera lights, linguistic thunder –lethal fatal insult by a security guard, “you pathetic, fatally miscalculated biological blunder”, savage dinosaur attack –barbaric men invading homes in “Blak Power” and killing of Bornfree, flight of a bird –white plane on the book cover (my version of the book) flying Darling to the garden of Eden (America), eating of the forbidden fruit –Aunt Fostalina’s infidelity to her husband and Darling’s car cruising with her friends, lion of Africa –Robert Mugabe according to Uncle Kojo, two hens fighting –Chipo/Darling Skype confrontation…Funny uh? That’s because I’m gearing you up for the next paragraph.

NoViolet also uses sacks-fulls of humour to engage you in her work and get you gripped from the very first page. And that begins right from her character names; Bastard, Chipo, Sbho, Stina, Mother of Bones, Fraction, Bornfree, Nomoreproblems, Forgiveness, Godknows, (names NoViolet dug out from God-knows-where!) The book made me laugh and laugh and then laugh some more. I remember it fell off my hands thrice. It’s definitely the funniest novel I have ever read and being a funny young man myself, I’ll always love this book more than even some other better crafted novels. Have a look at this scene in America.

I’m supposed to start teaching him my language because he says he and his brother are going to my country so he can shoot an elephant, something he has dreamed of doing ever since he was a boy. I don’t know where my language comes in – like does he want to ask the elephant if he wants to be killed or something? (P 268)

Okay if that didn’t hit your laugh button then what about this?

The boy comes up behind her, his thing like a snake in front of him. I reach forward and click on Mute because when the real action starts we always like to be the soundtrack of the flicks. We have learned to do the noises, so when the boy starts working the woman we moan and we moan and we groan, our noise growing fiercer with each hard thrust like we have become the woman in the flick and are feeling the boy’s thing inside us, tearing us up. We stop briefly when the woman takes her leg down from the railing and bends over, still grasping the pole. Now the boy is pumping grinding digging. We imagine he is fire and we scream as if we are burning in hell. Usually Kristal is the loudest because she has a high pitched voice but today Marina surpasses us all. (P 203/204)

The porn scene has captivated many readers. But this one below is darkly humourous.

He doesn’t tell us to say cheese so we don’t. When he sees Chipo, with her stomach, he stands there so surprised I think he is going to drop the camera. Then he remembers what he came to do and starts taking away again, this time taking lots of pictures of Chipo. It’s like she has become Paris Hilton, it’s all click-flash-flash-click. When he doesn’t stop she turns around and stands at the edge of the group, frowning. Even a brick knows that Paris doesn’t like the paparazzi.

Now the cameraman pounces on Godknows’s black buttocks. Bastard points and laughs, and Godknows turns around and covers the holes of his shorts with his hands like he is that naked man in the Bible, but he cannot completely cover his nakedness. We are all laughing at Godknows. (P 54/55)

I didn’t find the above picture taking funny, it instead irritated me a lot. Someone with a good heart will ask many questions and sympathize with the children rather than just taking photographs of them. How come an eleven-year-old is pregnant? Why is the little boy wearing a torn pair of shorts? Why are the children so slovenly? The camera lady in “Hitting Budapest” does the same thing. She throws away the thing she was eating to reach for her camera and take pictures of the hungry children when they wanted to eat the thing she was eating. The writer brilliantly illustrates how many whites and Asians come to Africa with only a “tourist view” of the continent; just to see our breathtaking landscapes, fluorescent flora, exotic beasts, get many pictures of whatever they see and leave quite blind to the suffering. So poignant! But she still succeeds to make it funny. She still pulls a laugh out of you even when she is writing about a funeral. Now that is what I call a reincarnation of ancient itinerant story tellers.

The book also contains the most virtuoso prose poetry I’ve ever read in my entire life. NoViolet’s prose is like boiling water with poetry evaporating from it like water vapour. Below are my favourites:

She is wearing a yellow dress and the grass licks the tip of her red shoes…The sun squeezes through the leaves and gives everything a strange colour…blue beads, their colours screaming against the quiet brown of the skin…The sun is already frying the shacks; I feel it over my body, roasting me…our stomachs are so full they could explode…It’s light rain, the kind that just licks you…The rain stops and the sun comes out and pierces, like it wants to show the rain who is who. We sit there and get cooked in it…listening to the cough pounding the walls…He feels like dry wood in my hands, but there is a strange light in his sunken eyes, like he has swallowed the sun…his legs are so hairy you could comb them…Now mother is moaning; the man, he is panting. The bed is shuffling like a train taking them somewhere important that needs to be reached fast. Now the train stops and spits them on the bed of plastic, and the man lets out a terrific groan.

Yes, very creative. And there’s no remedy to my addictive affinity for these lovely cascade of similes,

We didn’t eat this morning and my stomach feels like somebody just took a shovel and dug everything out…proud peacocks, the feathers spread out like rays…when Makhosi came back his hands were like decaying logs…we pass tiny shack after shack crammed together like hot loaves of bread…she is kicking and twitching like a fish in the sand…we are as sad as graves, sad like the adults coming back from burying the dead…their voices circle each other like crazy cocks…a fucking tsunami walks on water, like Jesus Christ, only it’s a devil…we watch the car like maybe it’s a bride…so thin, like he eats pins and wire…his voice rises like smoke, past us towards God…in America, roads are like the devil’s hands, like God’s love reaching all over…the singing is so distant it’s like the voices have been buried under the earth…Aunt Fostalina snatched the remote control from the coffee table pointed at the TV like it was a gun and shot…the calls just keep coming like maybe they heard Aunt Fostalina is married to the bank of America…staggering and bumping into stuff like a chicken with its head cut off…little kids over there riding that escalator like it would take them to heaven, their screams rising like skyscrapers…her voice sounds far away like maybe it was detained at the border or something…now they are just living together like neighbouring countries.

NoViolet’s English language is simple yet very admirable. There are also no inverted commas cloaking dialogue so the narrative marries the dialogue and they become one like husband and wife. There are a few non-English words in the novel too, generally stemming from the Ndebele language and the novel has that Ndebele sensibility to it. My favourite non English word will always be “kaka” which I later learnt means “shit” in the context of the book from social media. I was again amazed to find out that my “kaka” has got links to Spanish “Caca” which is from “mierda” which means “shit.”

The writing is more engaging in the Zimbabwe setting where Darling is very extroverted but as she leaves for the US which is a new environment she becomes introverted and quiet. This makes the writing to be less engaging. NoViolet’s writing also has a certain characteristic that delivers a great effect on the mind of the reader which I personally call “witty word repetition” like these…But that was not stealing-stealing because it was Stina’s Uncle’s tree…Forgiveness is not a friend-friend because her family just recently appeared in Paradise –this makes her a stranger…Paradise with its tin, tin, tin…then Father laughed, but it wasn’t a laughing-laughing laugh. You kind of understand what she means. Father laughed but it wasn’t that kind of explosive laugh that goes hahaha-hehehe-huikihuiki but a gentle sick one since it was coming from a pair of AIDS ravaged lungs.

So after writing a very flowery review NoViolet Bulawayo’s novel and her writing, wasn’t there anything for me to criticize in it? Definitely. I have a fat sporting problem here, Maybe my measles will be gone by the time it’s World Cup, then I can come and be Drogba. Hey, what about my compatriot, Samuel Eto’o? The most decorated African footballer of all times! Il est plus fort que ton Drogba, NoViolet! Quatre fois Ballon d’or Africain et trois fois gagnant de la ligue des champions Européenne! La légende Camerounaise du foot Africain! Qui est ton Didier? No, I won’t translate the French because NoViolet didn’t translate the Ndebele. All that is just humour anyway. The funniest novel in African Literature also deserves a funny book review. On a serious note, I felt the stronger and more engaging part of the novel is the Zimbabwe setting and the narrative lost some of its appeal in the US setting. I was also a bit irritated by the misandry in the novel, men are painted in bad light a lot. There is also the time flaw between the kids playing the find Bin Laden game and Chris Brown’s walloping of Rihanna which Ikhide Ikheloa raised in his brilliant review of the novel. To be honest, I don’t think I would have been as smart as brainy Papa Ikhide to spot that weakness. But then, is there any work which is error free? J.S Newman once said, “Nothing would be done if you waited until you could do it so well that no one would find faults.”

I have read about five different reviews in which the reviewers applauded NoViolet Bulawayo’s immense literary talent but projected her as a poverty porn star and accused her of writing her book in a “western-media-coverage-of-Africa” style, a CNN coverage of African anguish, “performing Africa” and including a string of clichés about African suffering which the world is already quite cognizant of. They have made their solid points and they are entitled to their opinions. But I disagree with all of them. Generally, writers get inspired to write about what moves them, from what they perceive, see, hear, feel etc. And in this particular case, “We Need New Names” was written by a young Zimbabwean woman who saw her once normal homeland where her family still resides burning and crumbling like a pack of cards from far away in the US for ten very painful years called the lost decade. She felt it was a very necessary project to write about the dystopia of that period, especially when it peaked in 2008. She says it, but I think the genius of this great woman is the fact that, she goes further to say and illustrate that the so called “single African story” is not only unique to Africa. Even America, mankind’s paradise on earth (hey, not that kaka Paradise near Budapest) is suffering from the same condition. She also clearly shows how the so called “single African story” may very well be a universal story, the lamentable condition of all humanity. Jesus Christ! We need new names and new geniuses like NoViolet Bulawayo.

About the cartoonist: Ebesoh Dexter is a final year Medicine student at the University of Buea in Cameroon. He’s a doctor in the making and an up-and-coming cartoonist who plans to revolutionize drawing in the field of Medicine by coming up with art of the numerous Medical textbook pictures and fiction characters in general from the animated cartoon angle. He lives in Buea, Cameroon

About the cartoonist: Ebesoh Dexter is a final year Medicine student at the University of Buea in Cameroon. He’s a doctor in the making and an up-and-coming cartoonist who plans to revolutionize drawing in the field of Medicine by coming up with art of the numerous Medical textbook pictures and fiction characters in general from the animated cartoon angle. He lives in Buea, Cameroon

About the author: NoViolet Bulawayo was born and raised in Zimbabwe and now lives in the US. She was shortlisted for the 2009 J.M Coetzee judged Studzinski award for her short story, “Snapshots”. Her first published story, “The Watcher”, was published in Munyori Literary Journal in 2009. She later won the 2011 Caine Prize for African writing for her short story, “Hitting Budapest” which also appears as the first chapter in her debut novel, We Need New Names. It was the only African novel shortlisted for the 2013 Man Booker Prize and she is the first black African woman to achieve the feat. Her work has been published in numerous anthologies, Boston Review, Callaloo and Newsweek. She earned her MFA in Creative writing from Cornell University in 2010, where she was recognized with a Truman Capote Fellowship. She is currently a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University.

About the author: NoViolet Bulawayo was born and raised in Zimbabwe and now lives in the US. She was shortlisted for the 2009 J.M Coetzee judged Studzinski award for her short story, “Snapshots”. Her first published story, “The Watcher”, was published in Munyori Literary Journal in 2009. She later won the 2011 Caine Prize for African writing for her short story, “Hitting Budapest” which also appears as the first chapter in her debut novel, We Need New Names. It was the only African novel shortlisted for the 2013 Man Booker Prize and she is the first black African woman to achieve the feat. Her work has been published in numerous anthologies, Boston Review, Callaloo and Newsweek. She earned her MFA in Creative writing from Cornell University in 2010, where she was recognized with a Truman Capote Fellowship. She is currently a Wallace Stegner Fellow at Stanford University.

3 comments for “Nkiacha Atemnkeng on “We Need New Names””