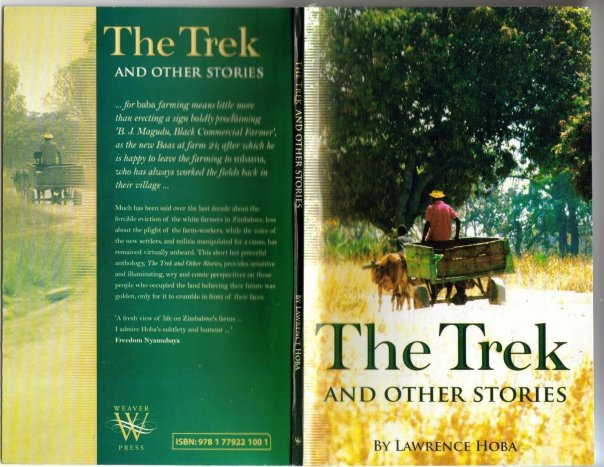

Lawrence Hoba was born in 1983 in Masvingo. He is an entrepreneur, literary promoter and author who studied Tourism and Hospitality Management at the University of Zimbabwe. Hoba’s short stories and poetry have appeared in a number of publications, including Zimbablog, the Warwick Review (2009), Writing Now (2005) and Laughing Now (2007). His anthology, The Trek and Other Stories (2009) was nominated for the NAMA, 2010 and went on to win the ZBPA award for Best Literature in English.

Munyori Literary Journal (MLJ): Your book’s focus is land, and early on you hint at the relocation to farmland in terms of it being like a return to the land of the ancestors. To what extent were your stories inspired by the land apportionment process of the 1930s, for instance? Or what historical periods were you specifically referring to?

Lawrence Hoba (LH): Indeed, The Trek and Other Stories focuses on the land reform. While these stories are focused mainly on the period between 1999 and 2009, it cannot be denied that the land apportionment processes of the 1930s set the precedence for a reverse occupation at a future date, given that these were the reason Black people had gone on to fight for liberation against colonial rule. However, in-order not to make the stories become a racial fight, there is only brief mention of the fact that the protagonists in the stories acknowledge that this was their ancestor’s land, which had been wrested away from them by the same people they were now driving out.

Thus, The Trek is about these people’s stories, not of their past, but their present as they try to settle back on their ancestor’s lands. They acknowledge they are no longer like their ancestors, and yet are not the same as their ancestor’s enemies either. They don’t consider those they are driving out as their enemies, but are acting to resolve an earlier evil, and regain what is rightfully theirs. The stories are about their daily struggles and triumphs.

MLJ: Why did you decide to conceive the land seizures of 2000 and beyond as a form of “trekking”?

LH: The land reforms of 2000 began with people going enmasse into the farms, normally in organised groups of villagers, towns people and war veterans. Some walked, some drove or were driven, some came on scotch carts into the farms. Firstly, this gave one the sense of this being a reverse trek. Whereas the 1900s had seen the Black’s ancestors fleeing the land, the early 2000s saw the White people fleeing and the Blacks resettling on land their forefathers used to occupy. This was more like the pioneer column which had trekked into the land in the late 1800s and invaded the same land.

Secondly, because there was no sense of finality to the occupation, with the government refusing to give Title Deeds to the new farm owners and instead leasing the land to all farmers, there was a general feeling (and there still is) that the land reform is not over. It is like a journey, a trek as it were, into the unknown; where one day you can work up and be told you no longer own the farm you got two days ago. Most people still have temporary shelters up to now, which is a sign that they are on the road. So until there is finality to the land reform process, the process remains a “trek”.

MLJ: What was your experience with these treks?.

LH: In February 2003, during my gap year, I went to teach at a school in a farm which had been newly occupied. The former white owner was still resident at the farm, and the new owners, about 500 families, were also setting up and farming. During that time, I saw people coming and going , others losing land they had given themselves because those who had been allocated by government authorities would have come with official letters and this inspired “The Final Trek” (resettling).

We all had to walk about 14kilometres to get transport into town. There was no clinic in a 20km radius, and I wondered what would happen with those who fell sick. I saw women who worked themselves to death planting and tending to cotton while some men chose to drink home brews, trap wild animals and set up bases to re-enact the liberation war system. There were other men who worked extra hard. I watched people fall in love, and others break up. And to me, each of these and many more cases was a small trek for the individual, the farming communities and indeed the country as a whole. It was a journey no one knew the end of.

MLJ: I’m glad you already started to address the roles men play in these stories. Can you talk some more about why most of the men are seen by the child narrator as lazy, always getting drunk while all the important work is done by the women? Is this a critique of something you have observed in Zimbabwean gender dynamics, or should the reader limit this observation to the scope of the specific stories in the collection?

LH: The stories are a reflection of a point in time; a time when as the author I had a higher consciousness to gender issues, and the gender dynamics persisting in the country. I grew up seeing some men who carried themselves as if they were the farm foremen over their wives and children. And yet these are the stories of specific characters, who do not generally reflect the whole society at large. Because at the same time, I grew up in a family where my father would cook for us and no duties were specific to women or men. And yes indeed, the men I sometimes saw in the farms got themselves sloshed on work days. And these are the men that I chose to write about.

MLJ: Along the same lines, women, though somewhat powerless, are presented as having the heroic qualities, or at least as more desirable. We have the loyal wife Mhamha, then the wild Maria who knows what she wants in “Maria’s Independence”. What gender roles were you observing here? Is this depiction driven by some social justice imperative, or were you showing this as the reality on the ground? In short, how do you view the gender roles of the characters in your work vis-à-vis those in the society upon which they are based?

LH: The issues of gender portrayal take on both a social justice imperative and a reflection of what was on the ground when I went onto the farms.

The stories are specifically meant to highlight the roles women have played in the land reform, roles that are sometimes forgotten and ignored because society favours the story in which the man is the hero. The women I met in the farms had zeal to till the land, and succeed. They are your “Marias” who defied all negativity and distractions to succeed where only men were thought to succeed. They were some who were lazy though, and appeared not to know why they had come onto the farms, but these were the minority.

As highlighted earlier, it is a social justice imperative, to honour women for all their hard work. But this is not done in a way that deifies these same women. Remember, the same Mhama leaves the farms maybe worse off than she came on to them, because she has now caught on the character of her husband.

The apparent powerlessness of the women is placed in the overall context of society, in which women are not given space or allowed to brazenly show their power. If they are to defy this norm, they face retribution. And yet, it is this apparent powerlessness in the face of men, that has given the women characters all the power they have.

MLJ: In “Specialization” you bring in a character who has been educated at the University of Zimbabwe (two of them actually), caught up in everyone’s helplessness in the new challenge of utilizing the land they have taken over. What is the significance of highlighting the narrator’s university education in this story?

LH: The story of the land reform was not one for the uneducated and politicians only. It was a story about a whole society and this included university graduates who found themselves graduating at a time when the economy could not offer them any jobs. The story also meant to highlight the shortfalls of the education system in offering solutions to the unproductivity on the farms.

MLJ: The failure to use the land productively is one of the main issues covered by these stories. Has the situation on these kinds of farms changed since the writing of these stories?

LH: I have recently travelled some parts of the country and I have noted that above all, there is now deliberateness in the way in which the farmers are approaching farming. Yes indeed, there is a great change in the productivity on the farms. Many people want to farm now, and the ones that are farming are earning themselves some good money.