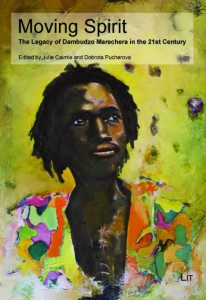

Moving Spirit: The Legacy of Dambudzo Marechera in the 21st Century

Moving Spirit: The Legacy of Dambudzo Marechera in the 21st Century

Edited by Julie Cairnie and Dobrota Pucherova, Published by LIT

Reviewed by Emmanuel Sigauke

There is Dambudzo Marechera the writer who died in 1987 and Dambudzo Marechera the collection of all the works by and about him. Books featuring critical perspectives on his works and those depicting his profound influence on contemporary writers have been published since his death. Moving Spirit: The Legacy of Dambudzo Marechera in the 21st Century is an example of such books, but it takes the Marechera tribute a step further: it moves it into the multi-media and digital climate of the 21st century. The book is an important contribution to the growing and insistent scholarship on Marechera.

Edited by scholars Julie Cairnie and Dobrota Pucherova, Moving Spirit is an academic work that features some of the papers presented at the 2009 Oxford symposium on Marechera, dubbed a “Celebration”, and better known in Shona culture as bira (in this case a tribute to a literary ancestor). The anthology is divided into three parts: “Inspired Creativity”, which consists of short stories inspired by Marechera’s writing or life; “Memory and Reflection”, in which readers of Marechera reflect on an aspect of their interaction with Marechera himself or with his work; “Scholarship”, which features essays by Marechera scholars from Germany, the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Canada. One of the most attractive features of the book is the “Afterword”, featuring Flora Veit-Wild’s revelation about her affair with Marechera in Harare in the eighties, an affair, as she points out, which was both risky and thrilling. The companion DVD is even richer; it contains audio-visual recordings of Marechera interviews, presentations and performances, as well as documentaries and performances which pay tribute to the literary icon. The book’s sections, in their diversity of perspectives, and the rigor or passion with which some of the contributors approach their subject, make for some interesting reading.

The contributors pay tribute to Marechera’s influence on their writing and scholarly work. They attest to his radical view of the world, the worldview of a writer who lived ahead of his time. In the prologue, Elleke Boehmer writes, “The free-wheeling verbal energies of Dambudzo Marechera were never to be contained within the moment of history he inhabited” (15). The addictive nature of is style is evident in the writing of some of the writers in the book, who in giving their tribute, attempt to appropriate his style. Boehmer states, “I found how Marechera’s shape had been grafted upon the imagination of the future; how he moved as a bemused and inspiring presence among us” (16). Indeed, throughout the book, the presence of Marechera is felt in the memories that each writer shares of Marechera the man, or Marechera the work. The book stays true to what it celebrates, the presence of the Marechera spirit in the twenty-first century.

In their introduction, the editors write, “Twenty five years after his death, Dambudzo Marechera’s spirit continues to haunt us.” In Shona culture, when someone dies, the family will perform the kurova guva ritual, which is meant to guide the spirit to the place where the rest of the family’s ancestors live, from where they visit and possess the living. One of the reasons for the ritual is to stop the spirit from haunting the living and wandering in strange spiritual realms. Perhaps the Oxford symposium on Marechera was a ritual to appease this literary ancestor’s spirit? And the book—this book—is a record of all the chants each literary family member made? Quite possible, but the analogy collapses when one realizes that a book this size cannot represent all the important scholarship and reflections there are on Marechera. In fact, one of the objections against the Oxford conference is how it didn’t include some of Marechera’s important contemporaries. Yet what the conference may have lacked could also be this book’s strength: that it has culled an angle, a premise to the study of the vast possibilities of Marechera’s work. The editors state, “This volume documents that Marechera’s Spirit is alive among us, moving across centuries to inspire us, disturb us, provoke us, laugh at us.” Of course, what we think his spirit does among us is all guesswork and myth, but the undeniable fact is that reading him has a profound effect on the reader, that the reader, in order to understand the work fully, has to connect with it emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually.

The editors contend that Marechera’s writing “invites re-invention” (19), that it is “performative and dissident” and “it plays with meaning and engenders new forms, myths and epistemologies” (19). This theme of reinvention is taken to heart in the whole book, as the collected works are a form of reinvention of the Marechera project. Each of the writers is involved in a form of re-invention, not only of Marechera the art, Marechera the writer, or person, but also of the writer’s essays.

Marechera has and continues to different writers and scholars, particularly in Zimbabwe. Memory Chirere, in his reflective essay, “Marechera-Mania among Young Zimbabwean Writers and Readers” covers aspects of this phenomenon. To Chirere’s freshman literature students at the University of Zimbabwe, Marechera symbolizes creative freedom: “Most of these students are for the first time exposed to freedom of mind and experimentation…Marechera’s rebelliousness offers a matchstick to the already growing desire of the students to be free from imposed ideas” (112). Chirere, however, notes that for these students, Marechera is a bad influence because they begin to miss lectures and assignments. Chirere also reveals that just as there is Marechera-mania among his students, the phenomenon also exists outside of academia, to ordinary readers on the streets, most who profess knowledge of Marechera without having read or understood his works. What they seem to embrace more is the idea of being associated with Marechera, being seen holding Mindblast or Cemetery of Mind, indeed to be known as followers of Marechera.

Nhamo Mhiripiri’s reflection is in the form of a poem entitled “A Letter to a Departed Buddy” in which he updates Marechera’s spirit on what has transpired in Zimbabwe. Most of the prophecies in his works have come true, the country has seen more rot, basically, pointing out that he was right all along, that indeed, corruption is widespread and the hunger is real. Here is a friend paying tribute to a departed friend, updating him even on all the post-humus work that has been published and continue to be published. There are other tributes like this, such as the one by performing poet Comrade Fatso, or the meta-fictional piece by Jane Brice. In these stories, or poems, Marechera walks in and out of the setting freely, much like a spirit, at once both visible and invisible. This is characteristic of the biographical nature of the work of Marechera himself. He is the kind of writer who will turn other writers autobiographical, laying bare the most private of their existence, some kind of dissection of the self, and which, in most of the stories in the collection, morphs into a double-dissection, of the Marechera spirit, and of the writer appropriating the Marechera style. Now, this is the performative that the editors talk about in their introduction.

Norman Vance and James Currey offer very revealing reflections on Marechera in Oxford. Vance was one of Marechera’s tutors at New College, and his account shows the difficulties Marechera fitting in. The Oxford environment was a hostile and stifling one to the creative Marechera. Vance also points out something very important, that a student-funded scholarship enabled Marechera to come to Oxford, but to many, including his Zimbabwean peers, his behaviour showed ingratitude. Writes Vance: “While the scheme was wholly benign in intention it could create awkwardness and resentment. Marechera was at times made to feel a beggar, sponsored by fellow-students he saw every day who might expect him to be grateful rather than difficult” (94).

James Currey’s piece is both a reflection as publisher of Marechera and of his participation at the Oxford Symposium in 2009. Currey admits that he learned a lot more about Marechera at the conference than he had while working with him as one of the contributors to the African Writers’ Series, noting that one important aspect of Marechera’s Oxford existence was that he joined the Romantic poet Shelley in being “thrown out of Oxford,” but Marechera, with his ability to “exploit liberal consciences”, was “relentless in his determination about never fitting in” (100). Marechera’s “impossible” behaviour is highlighted here; Currey admits that of the many writers he has published, “not one of them demanded such inordinate attention as Marechera.” Essentially, the writer exhausted his resources, his contacts, and his network. (He could indeed have benefited from a Facebook account! And he now does, considering that the Facebook page in his honour has over ten thousand followers).

The multimedia format of the book is a big attraction, as it digitizes and takes the legacy of Marechera into the 21st Century—it contains many hours of additional material, much work that makes the book seem like it is the extra material. In 1994, I watched Olley Maruma’s documentary movie After the Hunger and the Drought (1985) at the Zimbabwe International Book Fair, but I regret never having met Marechera in person. So going through the DVD was quite a treat, and it met this need in me, of hearing Marechera’s voice, as well as seeing him in action.

Readers will find the audio-visual material very revealing of a writer whose life has always been shrouded in mystery; the mystery of existence, with its deliberate orchestration, a writer who, aware of his artistry, defined his mythos, and a writer who did not allow any labels, yet with his emphasis on hatred of labels, he gained the ultimate label of a “writer against labels”.

This is indeed an important book, arriving at the right time, when the digital age may allow readers and scholars to reassess their positions on a literary icon. The book is an important introduction of Marechera studies to new readers, while providing new approaches to seasoned readers. The essays and memoirs helped me feel the presence of the Marechera spirit and made me realize that much still needs to be done to honour his legacy. And as long as the spirit continues to move, as is the nature of all spirits worth their name, then more books like this one will continue to appear, preserving and advancing the legacy.

4 comments for “Keeping the Marechera Legacy in Motion: A Review of “Moving Spirit””